Introduction to the Series

Together is a wonderful place to be. — Dwayna Litz

The Imperative of Our Times

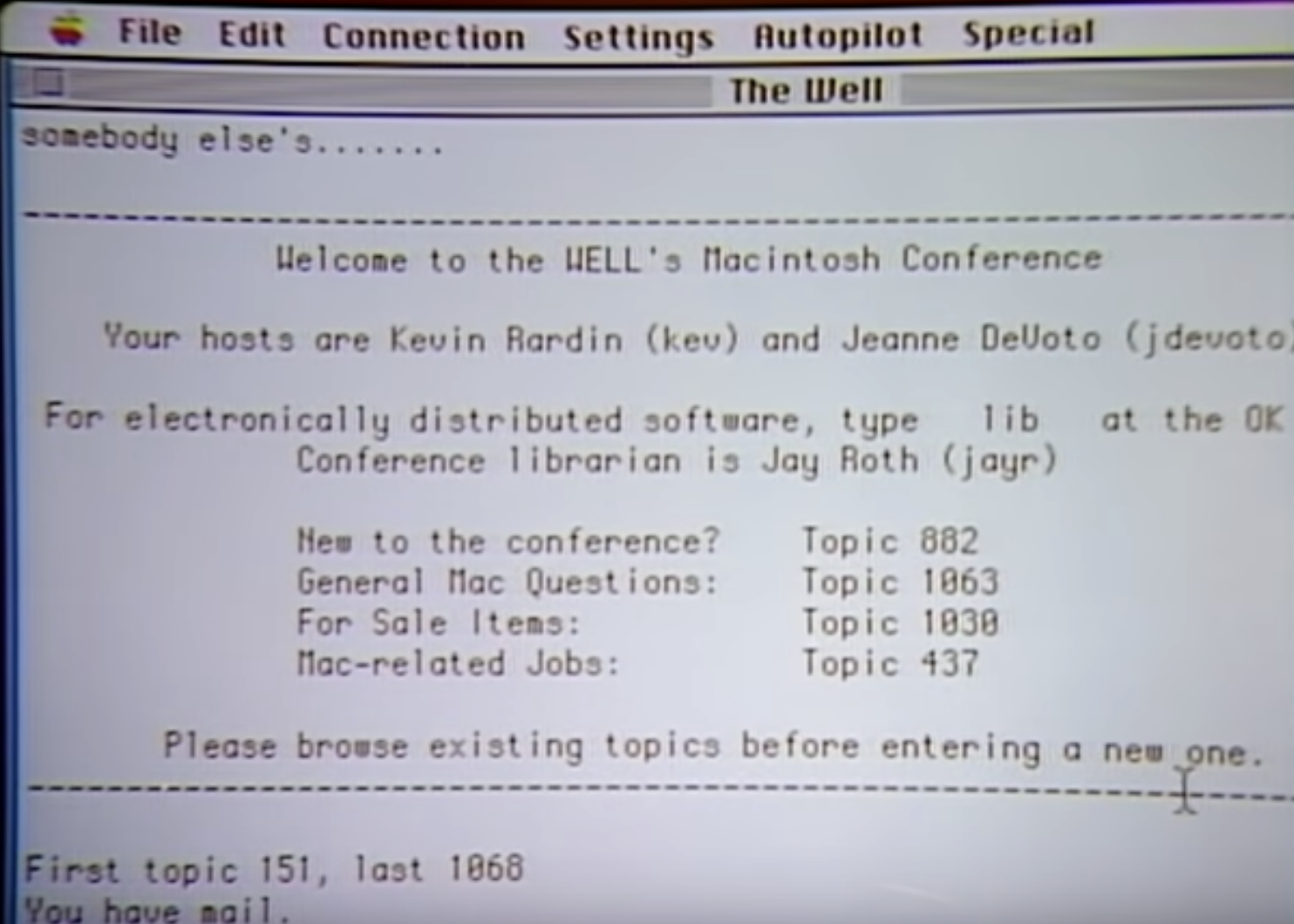

The Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link, or The WELL, is one of the oldest virtual communities that is still operational. Launched in 1985, it grew to 7,000 members and a staff of 12 full-time employees with a gross annual income of $2 million in just eight short years. These are interesting statistics, considering how the foundations of the modern-day internet — that enable such communities — didn’t exist at the time.

One participant of The WELL, Howard Rheingold, wrote a book aptly titled The Virtual Community, where he discussed the vagaries of life pertaining to online communities. The book’s prescience is uncanny.

Terminally online people, constant trolling, being there for each other, and even finding love were as common back then as they are now.

What’s more interesting, though, was the focus of Howard’s work. He wanted to investigate what made a digital message stream into a community as good as any other. When a conversation is stripped of its social cues, how does one create a feeling of warmth with words?

This series on community building tries to answer this question in detail. Exiting the domains of Big Tech, people today are increasingly turning away from mindless consumption. In a world of remote everything, people are seeking and creating communities that do things.

Be it WSB traders, DAO contributors, or activists in Signal groups, the meta of the times has been participating in and growing communities. This could be attributed partly to the nature of things — narratives that provide meaning to our lives have withered, leading to increased isolation.

The family that shared a single TV is now sitting separately with their screens. Technology has gone from a facilitator of “real-life” activity to a replacement of it. As a result, we are now finding meaning in these screens, which has turned participating in and growing virtual communities an imperative for our well-being.

Taking a Closer Look

There are several peculiarities to virtual communities. They are like data streams, sustained by prompt replies, a medium where multiple people can talk simultaneously and still make sense. Despite this, owing to the constancy of human nature, virtual communities aren’t much different from “real-life” communities.

They each have their set of participatory and initiation rituals and rules that facilitate the entry of the new and the exit of the old. They also go through the same stages of growth — ones that we will discuss in more detail in the upcoming articles — and face some of the same issues.

To be best prepared to understand and tackle these issues, we must closely examine some of the key ideas behind communities.

Communities are Gestalts

Great communities are gestalts, providing members with value they cannot access or create on their own. This is best witnessed in our usage on social media. A great chunk of the value of web2 social media, especially of UGC applications such as TikTok, Instagram or YouTube lie in the communities they foster.

The comments sections of each post indirectly add to your experience of consuming that piece of content. You may be able to consume that content elsewhere, but you certainly won’t get the same value out of doing so.

web2 social media comments sections — content can be consumed anywhere, but the community is only on the platform.

Communities are Living Beings

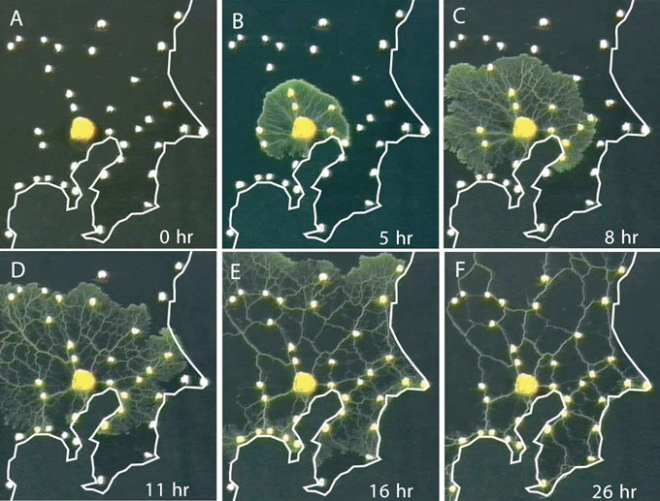

The best communities are participatory and emergent, and the best community builders approach their work as gardeners instead of builders. Taking this analogy forward, a great way to think about communities is by thinking about slime molds. That is to say, a community is never “complete.”

It will always be messy and ever-evolving, and each stage is beautiful in its own right.

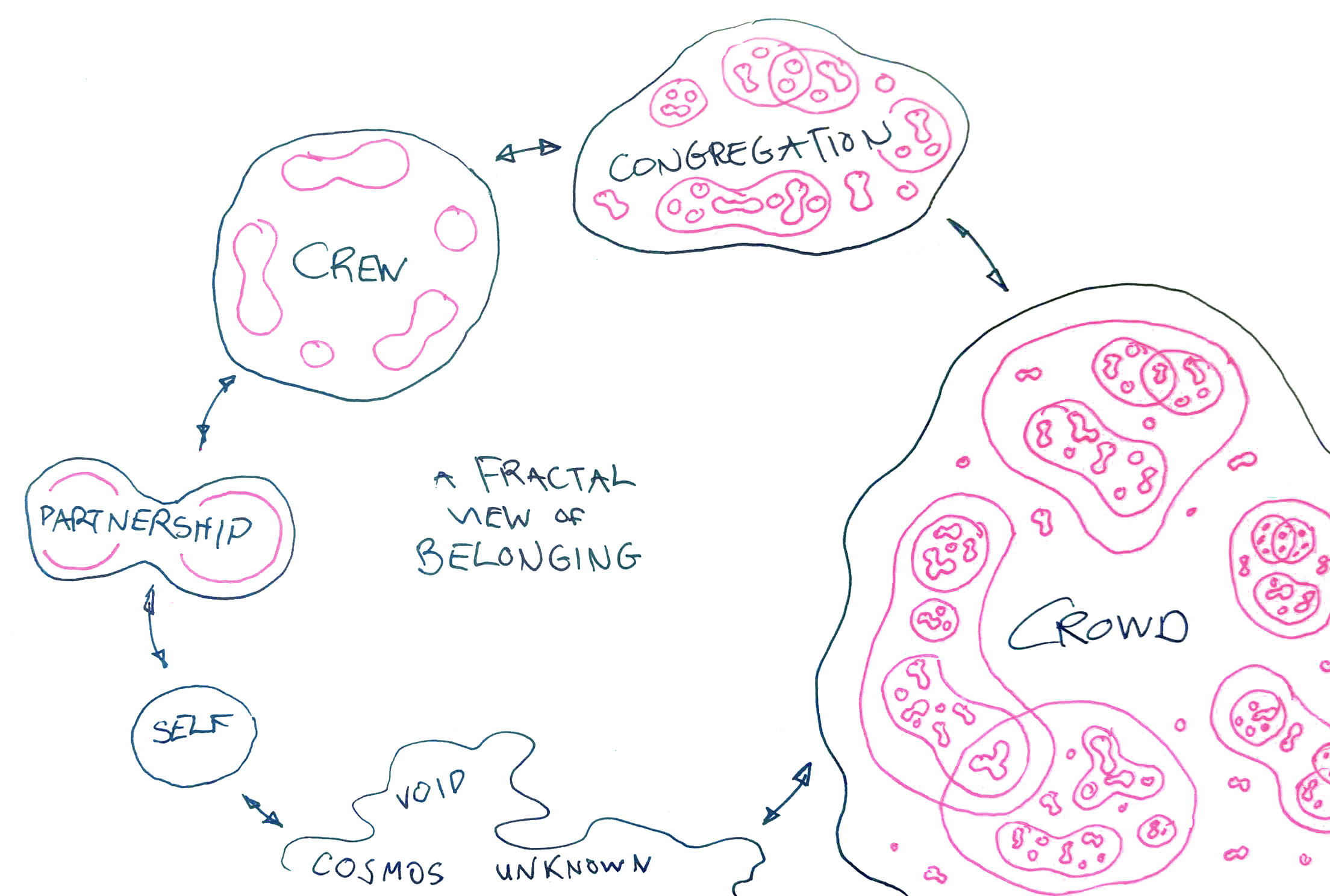

Communities are Spaces

Objectively seen, communities create spaces. The primary purpose of a space is to maintain a specific atmosphere for the people within, not the exclusion of those outside of it. A space is thus defined by its boundaries and rules that classify everyone into in-groups and out-groups.

This is a key concept to grasp.

If you approach spaces created by communities as something exclusionary, you create vulnerable communities with extrinsically motivated members who just aim to look good. However, if you approach these spaces created by communities as something that protects a certain energy, you create robust communities with intrinsically motivated members who are there for authentic connection.

What sustains a community?

Your community’s garden must be tended to regularly. These are vital activities that sustain communities in the long run.

Narrative Building

CCommunities that achieve things have compelling narratives greater than any one individual. It is a north star that attracts the right kind of people and facilitates decision-making and coordinated action.

The only thing more important than a compelling narrative, though, is the ability of members to contribute to it. Fortunately, the nature of virtual communities facilitates discussion and enables groups to decide and act on agreed-upon goals collectively.

The strongest communities encourage members to “take the story forward.”

Iterative Processes

As communities grow, it becomes more and more challenging to arrive at a consensus and get stuff done. That is why iterative processes focusing on consistent output close the loops faster and fight stagnation.

A “good enough” mindset is better than “the best.” Good enough work, iterated upon, has a higher chance of achieving its true potential than work that is painstakingly created trying to perfect every detail (or even just a few).

There was a fellow who kind of ran the mailing list, who died a few years ago by the name of Jon Postel, and everybody trusted him not to be in a particular faction. The philosophy behind the people who created the internet was rough consensus and running code. So the rough consensus is essential because anyone who’s participated in consensus-based activities that begin after strict agreement finds that they go on and on and on.

The Illusion of Control

Around the same time as The WELL, the first iterations of a metaverse were created by Lucasfilm in Habitat. Users controlled their avatars that moved around in a virtual world.

In a paper published by the programmers of Lucasfilm Habitat, titled The Lessons of Lucasfilm’s Habitat, Chip Morningstar and F. Randall Farmer talked about designing and managing this virtual community of tens of thousands of people.

Their main lesson from working on the project is as follows:

…*detailed central planning is impossible; don’t even try it. Create the tools for users to build their society, and let the users tell you what they want to do because that is what the users…will do, no matter how hard you try to structure some other purpose. The more people we involved in something, the less in control we were.

We shifted into a style of operations in which we let the players themselves drive the direction of the design. This proved far more effective. Instead of trying to push the community in the direction we thought it should go, an exercise like herding mice, we tried to observe what people were doing and aid them in it.* >

As community stewards, our job is to set the necessary context and background for a community to flourish. Initially, it may feel like you are in control since nothing happens that makes you think otherwise.

But as your community grows, you realize that the only way to reconcile the ensuing chaos is to give up any idea of control and aid the community in doing what it wants to do.

Moving Forward

Any community goes through four critical stages in its lifecycle. This series has four more articles, each concerned with one of the four stages. In this piece, we touched upon the history of virtual communities, our learnings from these experiments, and critical approaches to growing communities.

We must look at any community as a garden — an organic space that is ever-evolving and ever-changing. We need to have a compelling narrative that members can contribute to. We must consciously try to share power and always favor what’s “good enough” over “what’s perfect.”

So what does such an approach to community building look like? In the following posts, we shall go into the weeds, introducing new concepts, walking you through tactical exercises, and informing you about key roadblocks to expect and watch out for. LFG! 🚀